Written by Pardis Mahdavi, Provost and Executive Vice President, The University of Montana

These protests have echoes from past resistance movements. For the past two decades I have been studying gender and sexual politics in post-revolutionary Iran through on-the-ground ethnographic fieldwork. For some 40 years following the Feb. 11, 1979, Iranian Revolution, when Ayatollah Khomeini came to power and overthrew the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, people have been rising up against the brutality of the regime in both urban and rural areas.

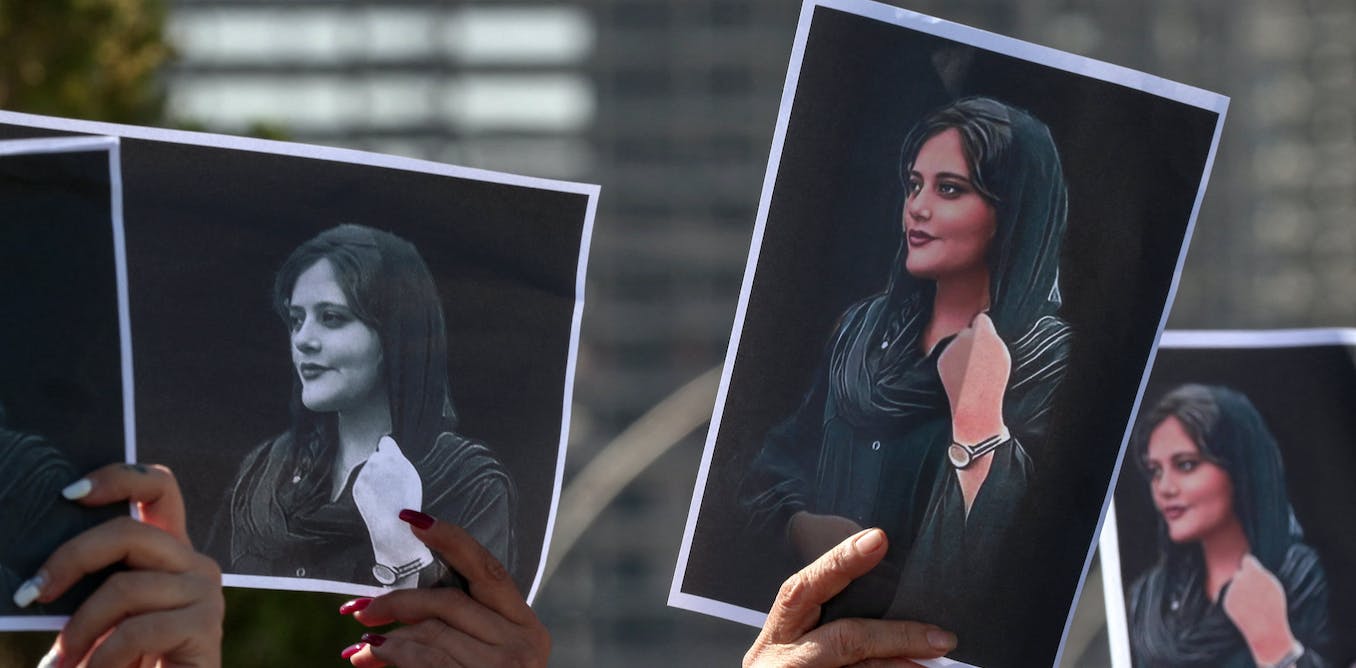

Today, these protests have been gaining increased momentum and international attention, giving many Iranians inside and outside of Iran some glimmers of hope.

Islamists’ resistance to westernization

Support for the Revolution grew out of many Iranians’ desire to bring equality and democracy to Iran. They criticized the monarchy as being overly deferential to the United States and were frustrated with increasing gaps between rich and poor.

The Islamists were most critical of westernization, which they saw as violating Islamic tenets and leading Iranians morally astray. They vowed to return Iran to Iranians and to re-center Iranian culture.

To do so, the Islamist regime juxtaposed its rule with everything that it believed to be wrong about “the West.” At the top of the list of critiques was what the regime viewed as loose morals. These loose morals were exemplified in the consumption of alcohol and women’s wearing miniskirts and heavy makeup and flaunting their hair and curves of their bodies in public.

As Khomeini ushered in the Islamists to power, a new era of austerity was born. Khomeini replaced the shah’s brutal police squad, SAVAK, with an equally if not more brutal Revolutionary Guard and created a new unit referred to as the “morality police.”

This era is perhaps best exemplified in the Khomeini quote that was painted across buildings and billboards in Tehran: “The Islamic Republic is not about fun, it is about morality. There is no fun to be had in the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

Controlling women’s fertility

Alongside the changes at home, Khomeini also engaged the country in a decadelong war with its neighbor Iraq.

Worried about the rising death toll coming out of the Iranian Revolution, combined with increasing numbers of soldiers needed for the Iran-Iraq war, the Islamists realized that they would need to increase their population quickly, according to demographic researchers. Thus, in the 1980s Khomeini instituted a series of policies in Iran to encourage families to have more children.

As a result, the birth rate in Iran in the 1980s swelled to an average of 3.5 children per family, up 30% from the prior decade.

A decade later, the Islamists realized that the population boom would need government support. Infrastructure would have to be strengthened and jobs created. The government did a complete turnaround and replaced its policy with family planning messages broadcast on the radio and television encouraging families to have fewer children. Sex education courses and free family planning resources were required for all couples who wished to be married. By 1994 the number of women using family planning was up 30% from 1989.

When the new millennium was ushered in, fully two-thirds of the country’s population was under the age of 21. These young people were born into the Islamic Republic of Iran that Khomeini and the Islamists had created: Women were told to wear long black cloaks from head to toe, covering every inch and curve of their bodies; the most brutal people were members of the morality police, watching every move and any strands of hair that escaped covering. If young people were found holding hands, attending a party or reading a book, they were deemed immoral by the whims of a mercurial regime.

This generation had never known the supposed opulence of the monarchy. And as its members became more frustrated and more educated, the critiques of Iran’s past drilled into them by the Islamists made less sense.

Challenging the morality police

Mohammad Khatami, who took over as president in August 1997, sought to harmonize Islamic rule with the needs of a changing population and a modernizing world.

Young people, who formed the majority of the population, had found their voice. They began challenging the morality police by pushing their headscarves back millimeter by millimeter, holding hands in public and organizing spontaneous street gatherings.

Between 2000 and 2007, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in the cities of Tehran, Shiraz, Esfahan and Mashad, following what young people referred to as Iran’s Sexual Revolution. The resisters demanded a more democratic regime focused on solving issues like unemployment and infrastructure challenges rather than on policing their bodies. During my research in Iran on sexual and social movements, I also had several run-ins with the morality police and experienced their brutality firsthand.

These young people’s revolution was fought through the language of morality using their bodies, their choices in outerwear, makeup and hairstyles. They defied the morality police by sliding their headscarves back, wearing layers of makeup and eye-catching outerwear, dancing in the streets and holding hands or kissing in public.

The government responded by cracking down and tightening its grip on the moral behavior of young people. Increased raids and public floggings were meant to send a strong message. But young people persisted in their resistance.

In 2005, when conservative candidate Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president, the sexual revolution came under heightened threat.

Unlike his predecessor, Ahmadinejad had no interest in finding ways to work with the growing youth population of Iran or in more progressive interpretations of Islam. He ordered the morality police to crack down on young people, raiding homes and parties and arresting women on the streets who dared to violate Islamist rules. Public floggings increased, as did arrests of scholars, feminists and journalists. The conservatives wanted to send a message.

The emboldened young revolutionaries continued pushing for change. These movements came to a head in 2009 when, despite not receiving the popular vote, Ahmadinejad was reelected as president.

Led by the same young people who resisted the morality police during the sexual revolution, a new movement was born in the immediate aftermath of the 2009 elections. This was called the “Sabze,” or Green Movement. People took to the streets of Iran chanting “where is my vote?” and “not my president.”

Marwan Naamani/AFP via Getty Images

A catalyzing moment for this movement was the chilling murder of Neda Agha-Soltan. She was killed in June 2009 simply for being at one of demonstrations where one of the bloodiest clashes between protesters, the Revolutionary Guard and the morality police took place. Her death was captured on film and shared with the world.

On the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution in 2019, the streets of Iran were once again filled with resisters, many of whom had participated in street protests since the early 2000s. These same children of the revolution and Iran-Iraq war organized efforts such as #MyStealthyFreedom that featured women photographing themselves without headscarves in public in Iran and joining the global #MeToo movement.

Demanding accountability

By 2019 disenchantment with the regime had spread from the highly educated young people in the urban centers to even many of the most religiously devout families in some rural areas who had been previous supporters of the regime.

Iranians of all backgrounds facing rising oil prices and unemployment as a result of years of sanctions were increasingly losing faith in their government. Many no longer subscribed to the rhetoric about restoring moral order.

Today’s street protests are taking place in more than 50 cities throughout the country and have drawn the attention and support of the international community. These protests are both a refrain of past protests as well as a renewal of courage and hope.

As in the past, since Sept. 16, 2022, activists are taking to the streets to challenge a regime steeped in a rhetoric of harshly interpreted morality rather than governing with the best intentions of the people. And as in the protests of 2009 and 2019, they are calling for accountability of the government’s shortcomings, as well as highlighting the poverty that rages throughout the country – along with the pain of the people.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.